Growing up on the rural New Jersey Bayshore, Jeff Harris loved to explore the wooded creek flowing through his great-grandfather’s farm. He and his family would roam the centuries-old forest and go canoeing, catching sight of turtles, otters, and beavers. Jeff bought the Mill Hollows Farm to keep it in the family, and he still likes to traipse through the woods.

“Some of the really big old trees, I remember seeing when I was kid. I go and revisit them all,” said Jeff.

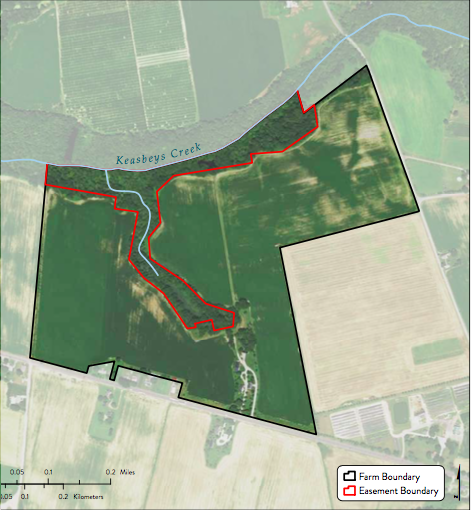

For generations, Keasbey Creek on the farm have been home to many fond memories. Yet Jeff and his family know very well that the creek offers more than recreational enjoyment—it is also part of the larger Delaware River water system that provides drinking water to 15 million people along the East Coast. The water system consists of rivers, wetlands, streams, and tidal marshes that are home to rare and vulnerable species of birds, fish, and plants. Waters from Keasbey’s Creek run through Jeff’s farm emptying into Mannington Meadows, a wetland critical for wildlife, and eventually drains into the Delaware River.

Jeff knows that farming, deforestation, and over-development can harm drinking water and wildlife habitats as a result of runoff from pesticides and other toxic chemicals. Protecting the creek’s water and ensuring the success of his farm are Jeff’s top and mutually beneficial priorities. That’s why Jeff decided to push the state to establish a permanent riparian buffer, a strip of land along the creek’s bank that acts as a natural filter for pesticides and other toxic chemicals, in order to protect the stream, woods, and wildlife. When he sought to sell his farmland to the state to prevent it from ever being developed, the State Agriculture Development Committee (SADC), the agency that administers New Jersey farmland preservation, denied his request to permanently protect the riparian buffer.

“The thing that I pushed for was the wildlife conservation on the wooded area. It’s especially important to me because I think that wildlife habitat is being destroyed,” Jeff told NJ.com.

Current New Jersey state laws offer legal protections to farmers looking to prevent their land from being developed. According to the SADC, there was a lack of clarity on whether or not those protections included the permanent protection of riparian buffers—the wooded creek in Jeff’s case. As such, the state offered to finance the conservation and monitoring of Jeff’s farmland but couldn’t ensure the trees along the creek would never be cut down.

Jeff approached the New Jersey Conservation Foundation, which in turn sought the support of the Open Space Institute and the William Penn Foundation to help finance the preservation of Keasbey Creek on the Mill Hollows Farm. Together, New Jersey Conservation Foundation and the Open Space Institute collaborated with the SADC to launch a pilot project that would serve as a model for future easement projects, which calls for the designation of special protected areas from urban development, of both farmland and bodies of water in New Jersey.

“It’s an important first step in a partnership with William Penn and its Delaware River Watershed Initiative,” said Susan Payne, SADC Executive Director. “We are very active in farmland preservation in the same areas these organizations are targeting for water quality in the Delaware Basin. Every time we do something new for the first time and hammer out a lot of precedent, it should make the next project easier.”

The public-private partnership between a local farmer, a state agency, and non-profit organizations was New Jersey’s first-of-its-kind effort but not the last. While farmland preservation programs the neighboring states of Pennsylvania and Maryland had already put in place water resource protections—a result of state and federal efforts to restore the Chesapeake Bay—New Jersey’s program had not yet implemented similar policies.

Many lessons were learned as a result of this innovative partnership. In addition to creating a model for future easement projects, the groups observed the need to continue building acceptance and interest among local farmers, increasing access to the funding for riparian buffer projects, and ensuring effective protections and monitoring. For many farmers, setting aside wooded creeks to protect local water can seem financially risky because it may require them to take some land out of production. Yet projects show that protecting trees along rivers and creeks can have financial advantages as well as the benefit of protecting drinking water. A key to the success in the protection of drinking water in New Jersey creeks and all throughout the Delaware River system requires the support and commitment of farmers such as Jeff.