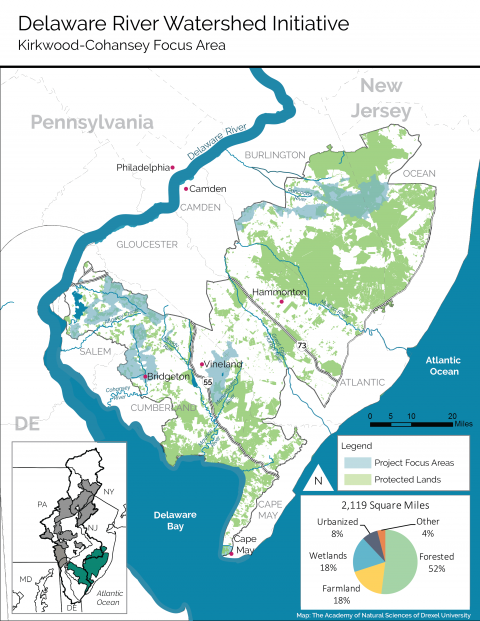

The aquifer underlies nearly two million acres—about one-third of the state— encompassing two large landscapes that have been the focus of effective conservation efforts for decades. These landscapes are the Pinelands, a globally significant biosphere recognized by the United Nations and designated by both the federal and state governments for extraordinary protection, and the Delaware Bayshore region, which includes New Jersey’s largest concentration of farmland.

Within the Pinelands are four major river systems. The largest is the Mullica River watershed— encompassing the Mullica, Wading, Batsto and Oswego Rivers—which empties into Great Bay and ultimately the Atlantic Ocean. The second largest is the Rancocas Creek watershed, which drains west into the Delaware River. The Great Egg Harbor River watershed, including the Great Egg Harbor and Tuckahoe Rivers, drains into the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, several small rivers in the Bayshore portion of this cluster flow through extensive agricultural areas and deliver fresh water into the brackish lower Delaware River and the Delaware Bay, including the Salem, Maurice and Cohansey Rivers.