The Paulins Kill and Musconetcong River are among the largest tributaries in New Jersey that drain to the Delaware River; these and the cluster’s other sub-watersheds capture a mixture of conditions representative of the Delaware’s more pristine headwaters as well as the heavily altered downstream portions further south in the basin. The entire New Jersey Highlands covers 1,343 square miles of the nationally significant Appalachian Highlands. It is part of the larger, federally designated Highlands Region that stretches from Pennsylvania to Connecticut, which contains one of the largest concentrations of intact forest on the east coast.

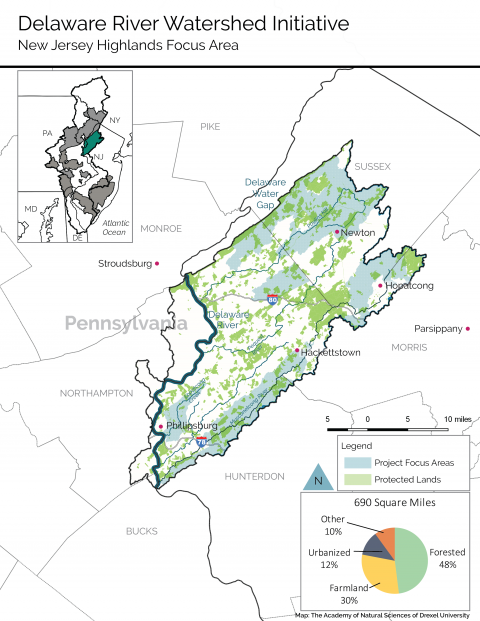

The New Jersey Highlands region is a vital source of drinking water for millions of people in the state, and in 2004, New Jersey adopted the Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act to systematically protect and improve the quality and availability of its waters. The New Jersey Highlands Cluster covers 690 square miles of this region, which represents the watersheds in New Jersey that drain into the Delaware River. The cluster is immediately south of the Poconos, with the Kittatinny Ridge as its northern boundary. Inhabited for more than 12,000 years, this region has been actively mined, logged and farmed for over 300 years, and cities and towns have grown alongside its rivers and lakes. Nevertheless, forests and wetlands cover more than half of the land in the New Jersey Highlands, and their preservation has been a focus of leading conservation organizations for several decades.