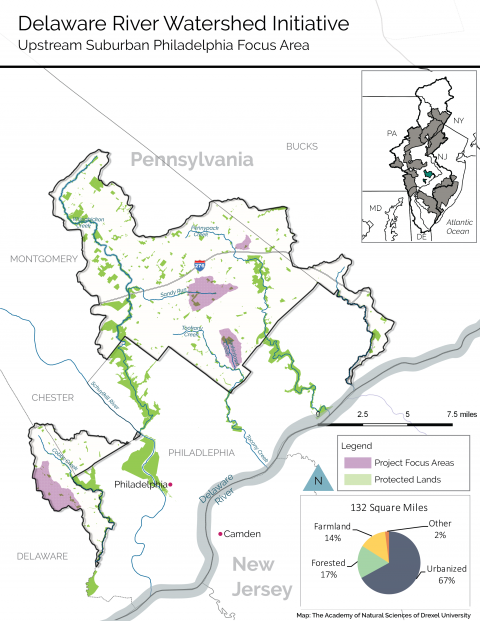

The Pennypack, Tookany and Wissahickon Creeks flow into the city from the northwest, while Cobbs (Darby Creek’s largest tributary) and Poquessing Creeks define the city limits to the southwest and northeast, respectively. These watersheds encompass 193 square miles, including 61 square miles within the City of Philadelphia, outside the cluster boundary. The cluster includes the upstream suburban portions of these watersheds in Bucks, Delaware and Montgomery Counties, where about 400,000 people reside. Learn more about the work in our watershed with this interactive StoryMap.

The waterways lie within the nation’s sixth-most-populous metropolitan area and are heavily urbanized. Most of the landscape is developed and has been converted to impervious surfaces—roads, parking lots, buildings—that generally cover from 25 to 50 percent of the landscape but can reach much higher percentages in town centers. The cluster’s streams flow through all or parts of 36 different municipalities including historic boroughs, as well as first- and second-class townships, governed by nearly 300 elected officials.

Almost all of the reaches of the cluster’s waterways are on Pennsylvania’s list of impaired streams due primarily to urban stormwater runoff and secondarily to excessive sediment and nutrient pollution. The region includes an extensive network of streamside parks and greenways that provide significant ecosystem services as well as recreational opportunities. Over 70 miles of walking paths and multiuse trails extend within and along the stream corridors of all five watersheds. Some notable examples are the greenway along the Pennypack and the Green Ribbon Trail along the Wissahickon.

Despite the important parks in the cluster, this area has extremely limited land available for protection, so the Initiative will need to achieve water quality improvements through restoration of degraded areas.

Urbanization fundamentally alters the characteristics of watersheds—their hydrologic cycle, riparian corridors, stream geomorphology, and assimilative capacity—thereby affecting water quality, water quantity, habitat, and ecosystems. “Flashy” stormwater erodes stream channels and leaves them choked with sediment and pollution. Efforts to improve water quality must be coordinated across multiple jurisdictions.

Urbanization fundamentally alters the characteristics of watersheds—their hydrologic cycle, riparian corridors, stream geomorphology, and assimilative capacity—thereby affecting water quality, water quantity, habitat, and ecosystems. “Flashy” stormwater erodes stream channels and leaves them choked with sediment and pollution. Efforts to improve water quality must be coordinated across multiple jurisdictions.