This past earth day weekend, a motley group of paddlers, including elected officials, photographers, naturalists, and friends, ventured deep into the New Jersey Pine Barrens to a white cedar swamp at the heart of one of Philadelphia’s most pristine sources of drinking water. Even in this untouched location, some refused to drink the water (this is after treatment with a $380 backpacking filter), citing a nearby air force base and the dangers of the known toxin and likely carcinogen, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). After all, it was just last November that New Jersey decided to regulate for this contaminant following its detection at unsafe levels in 12 drinking water systems.

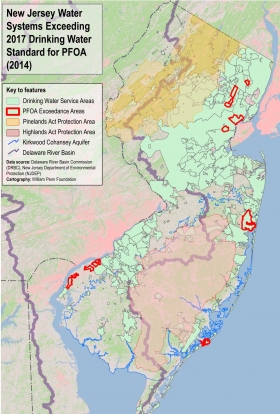

But while approximately 40% of New Jersey’s drinking water utility service areas are located in the Pine Barrens and Highlands (New Jersey’s other major protected landscape), not a single instance of hazardous PFOA contamination was detected in either of these two regions. This is not a coincidence. Both of these areas were specially designated to protect New Jersey’s drinking water supply. Policies in these areas incentivize conservation efforts like the protection and preservation of white cedar swamp and other important landscapes for water, and place limits on development and industrial activities that can easily pollute or deplete limited clean water supplies.

Landscapes in good condition may not as obviously signal the need for attention the way an old industrial site does, but they are just as important. Strategies such as the preservation of forests and open space, tree plantings, and the construction of rain gardens and other green stormwater practices protect our best drinking water sources, all while creating habitat for wildlife and increasing our resilience to the impacts of global warming. These strategies for water protection also present significant cost savings. The advanced treatment technologies needed to remove PFOA can cost up to $50 million per facility (according to a 2007 study commissioned by the New Jersey Department of Protection); a sum that could otherwise be used to protect and manage thousands of acres of forested and farmland.

Politicians can and should do more to protect these areas, but meanwhile, the local environmental community isn’t waiting– over the past four years, a team of New Jersey land trusts and watershed associations has been working together to address threats to water in the Pine Barrens from sprawling development, new energy pipelines, and even intensive off-road vehicle use. This work is part of a larger, 65-organization, $100+ million watershed protection movement that spans the entire Delaware River watershed. Launched in 2014 with funding from the William Penn Foundation, the Delaware River Watershed Initiative has created a framework that allows environmental organizations to better work together. By focusing on the same shared threats to our drinking water sources and aligning the ways we monitor water quality and healthy landscapes, this collaboration is accelerating conservation of these precious resources. In just four years, the collective work of these organizations has made an immediate impact on over 28,000 acres, and has helped leverage an additional $73 million from public and private sources for conservation efforts across the region.For the vision of a clean and abundant drinking water supply to be fully realized, it’s critical that we put in place forward-thinking policies to shape how we protect and steward the landscapes we live in. If we don’t, we’ll be forced to watch as pristine water sources become increasingly compromised and a dwindling clean water supply compels us toward progressively more expensive, and less reliable, alternatives. We have a wide variety of low-cost and readily available conservation tools at our disposal. Let’s put them to work.

-By Nathan Boon, program officer, William Penn Foundation

First published on Penn-ing Progress